China has, once again, instructed Bing to turn off the autosuggest feature of the search engine. The reason given by China’s State Information Office is, to quote from TheRegister article, that “Bad use of algorithms affects the normal communication order, market order and social order, posing challenges to maintaining ideological security, social fairness and justice and the legitimate rights and interests of netizens.”

I don’t know the details of why the Chinese government asked to remove autosuggest, nor whether and why Bing complied, but it seems to me that there is a lesson here for search engine operators and for people interested in algorithmic fairness.

Search engines are perhaps the most widely used internet service. They’ve replaced libraries for many of the information acquisition tasks we perform. When Google started, its stated mission was “to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful.” This implies that the results it provides reflect the world’s information. Indeed, many writers (e.g., this one in The Atlantic) wrote about the idea that search engines are automatic and reflect the knowledge available in the world. More recently, Google’s CEO said in testimony to the US Congress that “We use a robust methodology to reflect what is being said about any given topic at any particular time. It is in our interest to make sure we reflect what’s happening out there in the best objective manner possible. I can commit to you and I can assure you, we do it without regards to political ideology. Our algorithms do it with no notion of political sentiment.”

Unfortunately, as anyone in this business knows, a lot of manual work goes into an automated search engine. That manual work is done by people who have opinions, as do their managers. These people’s opinion can affect the results, and there is currently quite a lot of evidence that results don’t reflect the world’s knowledge anymore. Instead, they reflect the world as some people would like it to be.

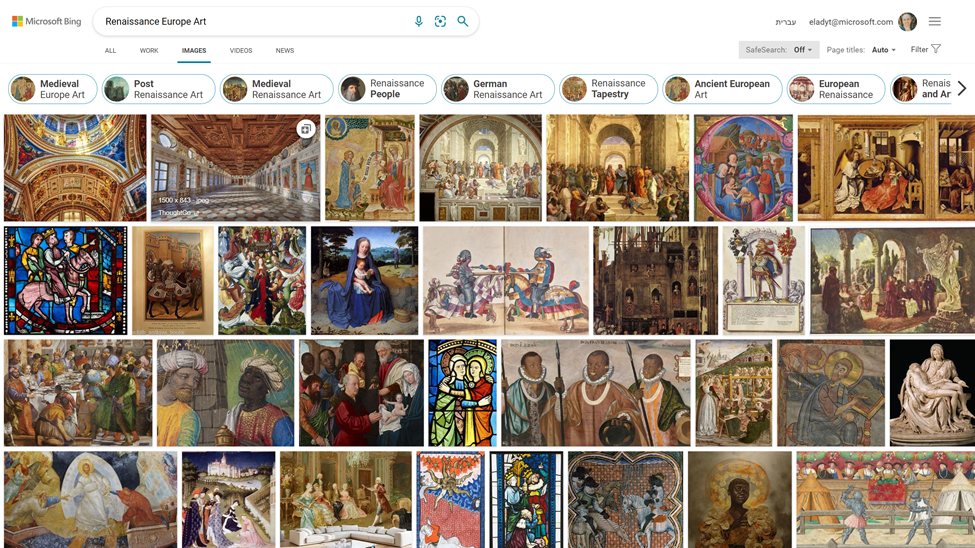

I could provide many examples that seem to have this bias, but let’s take one of my favorites: Consider the search results for the innocuous query “Renaissance Europe art” below. Before you do, think to yourself what art you think should be shown. Botticelli? The Mona Lisa? The Sistine Chapel?

Now click on the spoiler below to see a screenshot of the Bing results for this query.

Notice the preference for paintings of particular people?

It seems to me that governments have taken notice of the fact that “algorithmic results” are no longer algorithmic (and in fact, they probably never were entirely algorithmic). If results are human-generated, they say, why shouldn’t we, the representative of the people, decide what the results should be? Why should workers at internet platforms who may have specific views of the world get to decide that these are the “right” views?

This is a logical argument, though the devil, as they say, is in the details. If a government takes a heavy hand and decides to censor views it doesn’t like, what happens to how people learn about the world? There are parallels between this problem and that of book banning at public libraries (see, for example, this overview), especially now that search engines have replaced libraries.

It is hard to say if this situation could have been averted and if so, perhaps this Pandora’s box has already opened. But I do wonder if a little more modesty in changing algorithmic results would have prevented the place where we are at today.

I work for Microsoft, which operates Bing. The views in this post (as indeed, the entire blog) are my own and not those of my employer. I do not have any inside information on which queries undergo manual editing.