The other day I was talking to a friend of mine, a senior medical doctor at a research hospital. We were discussing clinical trials and how the recent staff shortages in the US made it difficult to start new clinical trials there. He mentioned off hand that clinical trials have been difficult to do in Europe for a few years now because of GDPR.

The European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation, or GDPR, is a regulation on data protection and privacy. It provides people with rights related to their data including, for example, the right to ask companies for data they collect about an individual (Article 15). GDPR is implemented in countries of the European Union, members of the European Economic Area and other countries which chose to implement it. The latter group includes Andorra, Argentina, Canada (only commercial organizations), Faroe Islands, Guernsey, Israel, Isle of Man, Jersey, New Zealand, Switzerland, Uruguay, Japan, the United Kingdom and South Korea.

The flip side of GDPR is that, for both companies and other organizations, it’s much harder to collect and process data. This may be a good idea when we’re thinking about companies which use these data to sell us more stuff, but it may be that these regulations have a less than beneficial effect for medical science. I wanted to see if there’s evidence for the latter.

In recent years medical researchers have begun registering their clinical trials on the US government’s ClinicalTrials.gov website. This can help patients find relevant trials, improve recruitment, and also reduce the likelihood of cheating (see Ben Goldacre’s wonderful talk on this subject). I took these data and extracted from them the country where each clinical trial is held (some clinical trials are held in multiple countries and I accounted for those) and the date at which it was first registered.

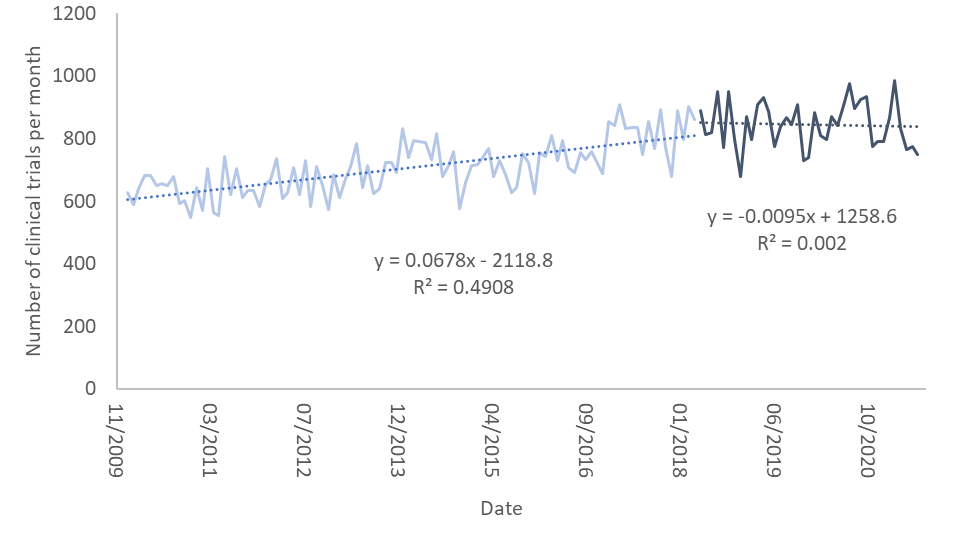

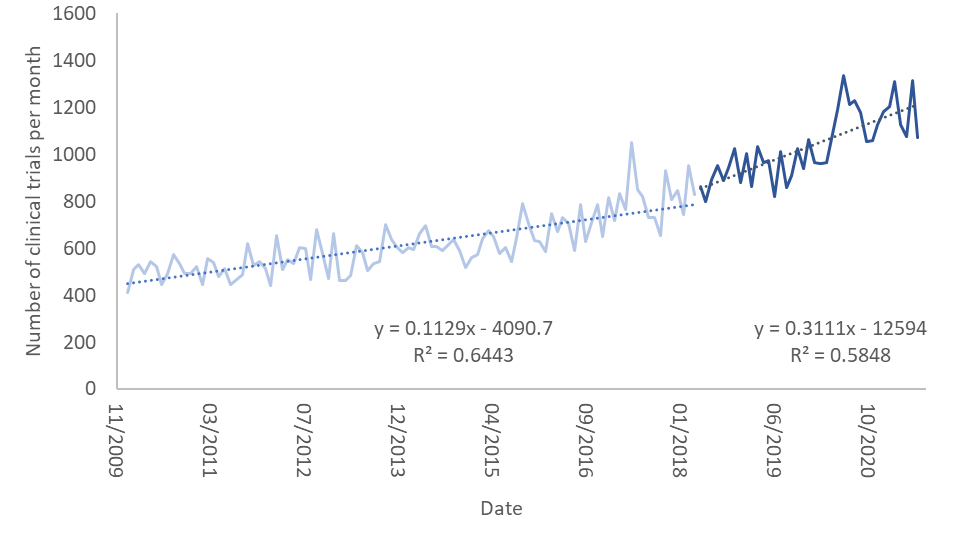

The figure below shows the number of clinical trials registered each month between January 2010 and July 2021. I divided the countries where the trials were held into three groups: the United States, countries where GDPR was implemented, and all other countries of the world.

In the graph the light colors are the number of clinical trials per month prior to the implementation of GDPR and the dark colors are the same numbers after it. I’ve also fit linear regression curves to each of these. As one can see, the number of clinical trials up to May 2018, when GDPR was implemented, rises slowly. Interestingly, it rises more slowly in the US than in the other two groups.

After May 2018 the rise in the number of clinical trials in the US and in countries where GDPR was implemented abruptly stops and flattens. However, in countries which did not implement GDPR (and are not the US), the pace of growth rises dramatically and accounts for the expected growth in both this group of countries and most of what we would have expected in the previous two groups. It seems as though GDPR put a break on clinical trials in countries where it was implemented, as well as in the United States.

Which countries benefited from this move from the US and GDPR-implementing countries? To test this, I computed for each country, the fraction of clinical trials conducted after the implementation of GDPR from all trials in the registry. I only looked for countries which had at least 500 clinical trials in the data. The 5 countries which had the largest fraction of trials post-GDPR are Pakistan, Egypt, Turkey, Indonesia, and China. Unfortunately, these countries are not bastions of human rights. According to Freedom House they are judged either “Not free” or “Partly free”.

Thus, it seems that one of the negative aspects of GDPR was the movement of clinical trials from countries which implemented it to those which did not. Whether this is a price worth paying is a personal judgment. To me, it seems that GDPR must be changed so that studies which improve the lives of people should be able to continue even at minimal cost to data privacy.

The current state of things reminds me of a story, possibly apocryphal, told to me by a lecturer during my graduate studies: A colleague of my lecturer who was a pain researcher from one of the industrialized countries took his sabbatical in Libya. This was, I think, in the late 1980s. My lecturer said that he asked the researcher, “why Libya?”. The reply was “it’s easier to do work there”…

Let’s not have GDPR cause medical research to move to countries which don’t take human rights seriously.

Caveat: I know there may be confounders that appeared at similar times. This isn’t a scientific paper, so take my explanations above with a grain of salt.